The Button

Monday evening, 8:14 p.m. Just as I’m getting ready to head up to put Melina to bed, my phone rings. A call from the place my parents live at this time of the night doesn’t bode well, especially when it’s not my dad doing the calling.

Monday evening, 8:14 p.m. Just as I’m getting ready to head up to put Melina to bed, my phone rings. A call from the place my parents live at this time of the night doesn’t bode well, especially when it’s not my dad doing the calling.

“Christina? It’s Pam. Your dad is complaining of chest pain. Should we send him in the ambulance?”

I look at Melina, who is waiting for me to braid her hair. Holding up a finger, I whisper: “Hold on.”

“Yes. Do you want me to meet him at the ER?”

“That would be good,” says Pam. “Where do you want me to send him?”

Pam and I decide that the closest ER would be the best one, and I thank her for her time. Melina learns that I won’t be putting her to bed, and within minutes, the twins and I are in the car.

“What happened?” one of them asks.

“I’m not sure,” I say. “I guess we’ll find out.”

Our town is small, and the hospital we chose is pretty easy to get to. Plus, almost five years earlier, I’d driven my dad to this same hospital. He was diagnosed with shingles then, and that diagnosis brought with it a whole chain of events that culminated in my mom’s diagnosis of dementia. So many images flash through my mind as I steer the car toward the parking garage and up the ramp. My hands and heart are steady, and I’m not sure why. Shouldn’t I be worried?

As the girls and I walk down the ramp, an ambulance pulls up to the doors.

“I wonder if that’s Dad,” I say. The three of us continue to walk but glance backward over our shoulders. Sure enough, Dad’s in the ambulance. He’s sitting up, his balding head reflecting the bright light of the ambulance bay. He can’t see me, but he seems fine.

“Maybe we won’t be here long,” I say to the girls.

***

The attendant calls us back to bay 35, where Dad is located. I peek through the curtains. He’s with a nurse, but she tells us to come in and have a seat. Dad’s color is good and he’s chatting happily with the nurse. He’s able to give her all the information she requests, and then, he apologizes to me.

“Sorry about this. I know you have a lot to do.”

“Dad,” I say. “It’s fine. If you have chest pain, you need to be seen. Did you push your button?”

Part of the monthly charge at the assisted living facility includes a call button. Dad usually refuses to use it, and I’m curious about this time.

“I did, but they took too long. I walked to the front desk.”

My mind spins again, impressed that Dad knew something was different this time. We don’t dwell on the differences, just sit and wait as clinicians, nurses, nursing assistants–they all come and go. And then, we see a doctor.

“Can you tell me what happened?” he asks Dad.

“I had this feeling across the top of my chest. A pressure, just for a bit. Really big pressure.”

“Did it go anywhere else? Down the arm, up the neck and jaw?” the doctor says.

“No. Just right here.” Dad moves his hand across the top of the chest. “It wasn’t very long, but it gave me enough concern to call someone.”

“And what did it feel like again?”

Dad recounts what he felt like. The doctor listens and nods then takes his stethoscope and puts it to Dad’s chest. He palpates the skin over dad’s breastbone. He looks at this arms, his legs.

“You know, this doesn’t sound like the classic heart attack. It could be nothing, but we’ll run some blood work and look at the EKG. My guess is you’ll be heading home tonight, but sit tight. This might take at least another hour.

***

My bum is starting to smart, and I’ve sent the girls home. They have school in the morning, and the clock is ticking. Well past midnight—I’m beat, but dad’s eyes are wide open. He won’t say much, and I wonder what he’s thinking

“How you doing?” I ask.

“I’m okay.”

“Then maybe get some rest? You might need it.” Dad reclines his head against the bed, and I arrange his T-shirt and jacket on the cabinet, resting my head against it. I’m glad he’s okay, but I’m also tired. Getting up early is something I always do, so the day has been long. But I have no complaints. Dad is alive. Fatigue I can deal with. Anything else? Not so much. I close my eyes.

Minutes later, Doc comes back in the room.

“Well, his troponin levels are up.”

“They are?” I ask. I’m surprised. Troponin is a protein specific to muscle, and cardiac muscle has its very own kind. When heart muscle is damaged, it releases troponin into the bloodstream. Despite the fact that dad looks great—good color, no shortness of breath—the presence of the troponin means he’s got some heart damage.

“They are. And we’ll be admitting him.”

I explain what “admitting” means to dad and make it home just before one in the morning. My mind refuses to shut off, and I fall into a restless sleep just after one-thirty. When the alarm rings at five in the morning, I roll out of bed and haul myself to the kitchen, hopeful that the coffee will make the day bearable.

***

I arrive at the hospital around ten in the morning. Dad is in bed two of a room on the cardiac unit. He’s sleeping and looks older, more frail than I’ve seen him in a while. The nurse doesn’t give me much information, only that his troponin levels are still rising and he’s scheduled for a cardiac catheterization that afternoon, at a time when the kids need to be picked up and driven to various activities.

“Can I go with him to the procedure?” I ask.

“He’ll be prepped about one. If you come in then, you can go down with him and stay in his room while they do the procedure elsewhere.”

I’d hate to send Dad to a procedure by himself. I call Tim and ask him if he can take the afternoon off, get the kids where they need to be. He agrees, and my mind settles a bit. I sit with Dad for a little while, but he’s sleeping, for the most part. I wake him to tell him I’ll be back, and then I go home, ready to open email or do something that doesn’t involve dad’s health. Maybe I’ll even take a nap.

***

Back at the hospital just before one in the afternoon, Dad looks okay. He’s tired, but he hasn’t eaten, and he’s getting a bit annoyed at the waiting. Once he’s been sent down to the cath unit, he has to wait even more for the procedure.

“Dad,” I say. “This is what happens in hospitals. Maybe an emergency came up. We’ll get there. Don’t you worry.”

But as the minutes tick by, and the early afternoon slides into late afternoon, I begin to wonder. Will they get to him today?

When I return from the bathroom, the crew is there to take Dad to the procedure.

“You should have gone to the restroom an hour ago,” Dad jokes. It’s good to see him in his usual form. Apparently, whatever is wrong with his heart can’t be that bad.

“I’ll see you in a bit, Dad.” I smooch the top of his head and then step back and wave. I haven’t discussed the risks of stroke or anything else with him. Gina and I mentioned it on the phone earlier in the day to him, but right then, I just wish him well.

Forty minutes later, I get a page that Dad’s finished and before Dad even returns, the cardiologist pokes his head in. He’s young and wiry with bright eyes. Just the sort of doctor I’d like to have on my case.

“I’ll be right in to chat,” he says. “Don’t worry.”

I’m not worried, just curious what he’ll say. The procedure is something I’ve discussed countless times with past students, but I’ve never been on this end of it before. Until then, that procedure remained in the textbooks I used to teach.

Before I can ruminate further, the doctor is back. He introduces himself, shakes my hand, and smiles.

“It’s a good thing I didn’t wait until tomorrow to work on him,” he says. “I might be delivering other news. Let’s take a look!” He hoists himself up on the counter and keys some information into the computer. He pulls up a few videos.

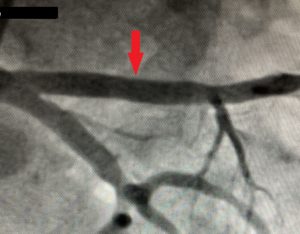

“This was the blockage: ninety-five percent in the Widowmaker!”

I’m speechless. I know what the “Widowmaker” is and why it’s called that. Dad had looked great the night before. The ER doc had thought maybe he’d be sent home. Thank goodness for troponin tests.

“Holy cow,” I say as the image of my dad’s heart pulses on the screen.

“But I put a stent in and look how beautiful this is now!” the doctor smiles again, and I’m floored by the difference.

When Dad returns, I tell him the news and show him the pictures, tell him he’s pretty lucky. His face blanches, and then he smiles.

“I guess it’s good I hit my button, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is, Dad. Yes, it is.”

Picture of stethoscope and EKG by Hermes Manuel Cortés Meza at Pixabay.com.