Struggling with Acceptance: An Interview with Catherine Shields

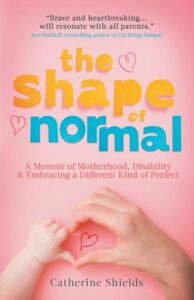

Catherine Shields is an author who answered my call-out on Instagram regarding upcoming interview slots, and I’m so glad she did! While I don’t write memoir, it’s one of my preferred reading genres, and her debut, The Shape of Normal: A Memoir of Motherhood, Disability & Embracing a Different Kind of Perfect, is at the top of my TBR list. She also writes Motherhood In the Margins, which is “a monthly newsletter about the joy and challenges of raising a child with a disability.” Both Cathy’s book and her newsletter are touching and informative, and the book was just announced as the 2023 winner of the American Writing Award in the Parenting category. At this time of the year, life is filled with so much, and I’m thankful Cathy found the time to answer my questions.

Catherine Shields is an author who answered my call-out on Instagram regarding upcoming interview slots, and I’m so glad she did! While I don’t write memoir, it’s one of my preferred reading genres, and her debut, The Shape of Normal: A Memoir of Motherhood, Disability & Embracing a Different Kind of Perfect, is at the top of my TBR list. She also writes Motherhood In the Margins, which is “a monthly newsletter about the joy and challenges of raising a child with a disability.” Both Cathy’s book and her newsletter are touching and informative, and the book was just announced as the 2023 winner of the American Writing Award in the Parenting category. At this time of the year, life is filled with so much, and I’m thankful Cathy found the time to answer my questions.

Christina: Congratulations on the release of The Shape of Normal. What made you decide to tell the story in book form? Why memoir in particular? Did you ever think about fictionalizing the story?

Cathy: I wrote this story in response to the years I spent haunted by the experience of hearing my daughter was “profoundly retarded.” Those were the exact words used by a neuropsychologist who explained we needed to hear the hard truth. But when it happened, I refused to believe him. And that phrase stuck with me for years.

As a kid, I always enjoyed reading books and could sit for hours in my dimly lit closet’s reading nook. I would make up my own stories about princesses who needed rescuing. As a teenager, I’d write in journals. Although I didn’t set out to write a book, I was interested in children’s literature. I majored in elementary education and became a kindergarten teacher. When my three children were little, I thought about writing children’s books, tried my hand at writing fantasy stories, then switched to creative nonfiction.

They say, “Write what you know,” so it was easy to talk about my own story. I didn’t know then what shape this story would take. I just knew that it revolved around the slow-moving mayhem of family life. It never occurred to me to fictionalize it; I wanted to tell the truth about my experience with motherhood—which had always been the most important thing to me—but I also wanted to vent.

Christina: Speaking of venting . . . writing can be therapeutic, and I take it you found it to be so. Did you learn something as you went through each stage of the writing process, either about yourself or your daughter?

Cathy: Writing the memoir helped me vent some of the pent-up frustration I felt. I spent a long time tortured with denial, and so when I started writing this story about fifteen years ago, I wrote with the intention of releasing that emotional burden. I learned I’m not afraid of facing my demons, that even though I was often frustrated and angry, I was able to live with that challenge. The last thing I have learned is that love was the guiding force in being a mother. It was hard (and is still) hard to parent a unique child, although I still struggle with complete acceptance, but I understand one can live with contradictions. It is part of life.

Christina: Jessica was still young when you found out that she had severe intellectual disabilities due to a birth injury. That news had to be gut wrenching, and as you said previously, “you refused to believe him.” Did the news surprise you? When did you get the first glimpse that Jessica was differently abled than her siblings?

Cathy: Early on, it was difficult to acknowledge that Jessica was not developing at the same pace as her twin sister. Oddly, she met each developmental milestone at the last possible minute. For example, a child should be walking by eighteen months and Jessica passed this milestone by walking (albeit with an unsteady gait) at exactly eighteen months. For the first two years, her pediatrician told me he wanted to wait and observe, so I chose to believe him. But when Jessica turned two, and her delays were obvious, he sent me to see a neurologist. That’s when she was diagnosed with mild Cerebral Palsy. The diagnosis happened in a time when there was no internet and the only thing I knew about CP was based on images from television fundraisers for severely physically impaired children. That’s probably why I was entirely focused on believing that with therapy Jessica could “recover” and be normal.

At three, she started an early intervention program. She was cognitively delayed but it was still too early to determine an actual IQ. When Jessica was four and a half, I received that devastating diagnosis. As I sat in front of that doctor and heard his pronouncement, the dreams for everything I had envisioned for my family vanished. It’s thirty-five years later, and the shock still hasn’t worn off. I responded with instant denial. A denial so strong, it resembled a mental disorder. It took years to recover and work my way to complete acceptance. Of course, on the intellectual level, I understood what the test results reflected, but I couldn’t imagine this as my reality. Jessica’s twin would move forward and leave her sister behind. I had to wrestle with the concept of what defined normal.

I was adamant that I could change the outcome. To the outside observer, it wouldn’t have made any sense, like a belief in raising the dead. Anyone who questioned my determination made me angry. My mother-in-law, who was my biggest supporter, kept encouraging me to seek alternative treatments, so this made it easier for me to remain in a state of denial and refuse to face facts. I took Jessica to therapies, schools, programs and sought out every resource I could find to “fix” Jessica and bring everything back to normal.

Christina: It’s so easy for humans to compare circumstances, things, people. With Jessica being a twin, did you find yourself comparing her to her sister and vice versa? Did you compare your parenting experience with your older daughter to your parenting experience with the twins? Do you think you would have approached the situation differently if Jessica had been born before your older daughter?

Cathy: It was only natural to compare Jessica to her twin, and to what her older sister did at the same age, which led to even deeper frustration. At the same time, it also made me determined to turn things around.

Not only did I have to deal with the emotional and physical demands of caring for this child, I felt remorse for the attention that was diverted from my other two kids and my husband. My other two kids were doing all the typical childhood activities. I felt jealous of the mothers who had “normal” children. I resented them for having it so much easier and then kept it to myself, making me feel further isolated. The resentment grew because of Jessica’s inability or unwillingness to participate in family-oriented activities. I felt judged by those who lacked understanding of her differences. I was an “outlier.” Thank goodness I had support and information from the other parents who were raising children with differences, yet even though that helped, I was stubborn.

I’ve never thought about how I would have approached the situation if Jessica had been the firstborn. The experience changed me. If she had been born first, I don’t know if I would have done better or worse. I needed my older daughter to act as an intro to parenting. The experience of having a child with a disability forced me to grow.

Christina: As you’ve said, acceptance is something you (like many others) have struggled with, and it’s something you’ve written about in a piece on Manifest-Station. There, you wrote, “It might take the rest of my life to learn the art of acceptance.” Where are you on that journey? Is it something that ebbs and flows for you? Are certain things easier for you to accept than others?

Cathy: One thing that’s been the hardest to accept is that I cannot take my daughter on family vacations where we have to travel by plane. She doesn’t like flying, gets hysterical on takeoff and landing. She also winds up vomiting and crying the whole time. It’s embarrassing to be given dirty looks from fellow passengers, and I feel like there’s a certain way people view others who look, talk, or behave in ways that are obviously different. I wish I could say I completely accept this, but I still struggle.

Then there’s the guilt. A few years ago, after my husband and I flew out of town to go camping with my oldest child and her family, a hurricane barreled into Florida. Jessica was living in the group home. The staff told me they had supplies and a generator, but if they were told to evacuate, Jessica would be going to a shelter. I thought I was the worst mother ever to have abandoned my thirty-year-old child. I called her every day, but cellphone service was terrible, and I worried almost the entire time we were away. Then we had the pandemic. When she got sick with Covid, I had to make decisions about whether to keep her home or have her remain at the group home. I don’t think I will ever get over this struggle.

Christina: Your piece in Brevity resonated with me, especially when you said, “I know I am not Jessica’s voice, but I can be her amplifier.” How long did it take to come to that conclusion? What can readers and community members do to serve as amplifiers too?

Cathy: I’ve always believed in trying to help children learn to be autonomous, so the answer to your first question is—it was a natural part of how I mothered. I always saw my daughter as an individual with her needs and wants, and I was determined for her to express them however she could. I think readers and community members should recognize we need to see people with disabilities as someone with differing abilities, but not different. There’s room for everyone at the table.

Christina: You’ve written a bit about rejection and the publishing industry. What made you decide to pursue a small press? What did you learn from your publishing journey? Will you tell us a little bit about the journey overall?

Cathy: I began by querying agents and when I had sent out fifty of these without one request, I realized my manuscript needed more work. The first editor I hired had some experience- and I hired her based on a couple of factors. She published with one of the big five, and her rates were so reasonable I thought it was worthwhile. After two rounds of edits, she pronounced my book ready. I sent out sixty more queries and received one request for a full and two weeks later, a rejection. I had sent one hundred and ten queries by this point to agents and that’s when I decided to switch to small presses.

I wasn’t sure if I’d ever get my book published, but I believed in this story and thought it had universal interest; the theme—learning acceptance. I started querying the small presses, had some luck with them, but learned many of them were hybrid presses (where the author pays upfront to have her book published and receives a large percentage of the royalties from sales.) I didn’t want to choose that. I thought if my book was well written, it would be accepted somewhere. I sought out another editor, a well-known instructor who came highly recommended. Her “sculpting” of my manuscript almost made me cry. The opening scene disappeared; the one everyone told me had to remain for my hook. But after three rounds of edits, I had ten requests for the full based on my opening pages. A month later, I had two offers from small presses.

Christina: What’s next for you?

Cathy: I’ve decided I am going to write about the mothers in my family. The ghost of my maternal grandmother will be the narrator of this story, and she’ll walk the reader through her early life up until mine. I feel like I want to continue a saga I’ve only begun to explore.

Cathy can be found in multiple places!

Website: https://www.cathyshieldswriter.com/

Instagram: @cathyshieldswriter

Facebook: @cathy.p.shields.3

Newsletter: Motherhood in the Margins

Thanks to Cathy for agreeing to this interview! If you know of an author or artist who’d like to be featured in an interview (or you would like to be featured), feel free to leave a comment or email me via my contact page.