Standing Up and Speaking Out: An Interview with Paula Dáil

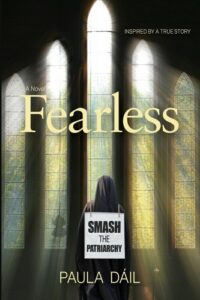

Author Paula Dáil came to me via Warren Publishing, which released her novel Fearless last year. The book won the Literary Titan Gold Star Award and the Reader’s Choice Silver Star Award, and it’s been called a “must-read” and “strong-willed, feminist novel.” One reviewer wrote, “You will be entertained, inspired, and then you will think, realistically, about one of the most controversial topics that is the highlight of discussion in American politics,” and another said, “Books with these kinds of empowering, realistic messages are much needed in the oppressive world of fake news and false rhetoric we live in.” Yes, we do need books like that, and I’m grateful for authors like Paula who are compelled to write them. I’m also grateful that Paula found time in her busy schedule to answer my questions so thoughtfully.

Author Paula Dáil came to me via Warren Publishing, which released her novel Fearless last year. The book won the Literary Titan Gold Star Award and the Reader’s Choice Silver Star Award, and it’s been called a “must-read” and “strong-willed, feminist novel.” One reviewer wrote, “You will be entertained, inspired, and then you will think, realistically, about one of the most controversial topics that is the highlight of discussion in American politics,” and another said, “Books with these kinds of empowering, realistic messages are much needed in the oppressive world of fake news and false rhetoric we live in.” Yes, we do need books like that, and I’m grateful for authors like Paula who are compelled to write them. I’m also grateful that Paula found time in her busy schedule to answer my questions so thoughtfully.

Christina: You’re a prolific author, with Fearless being most recently published in 2022. That novel tackles the theme of reproductive rights, which, unfortunately, are under attack here in the United States and elsewhere. You’ve gone on record as stating that reproductive rights have concerned you from the time you were young, when you “realized that without control over her reproductive life, a woman has no control over her life at all.” What made you write about the topic at this point in your life as opposed to earlier?

Paula: One of my favorite quotes is “One is not born a woman – one becomes one” by French feminist Simone de Beauvoir. One becomes a woman only to the extent she has control over her life, especially her reproductive life; otherwise, she is a puppet controlled by a puppeteer who makes her do what he wants her to do.

But to the point of your question: for all of my adult life, up until a year ago, birth control, including abortion, has been widely and legally available. Except for observant Catholic women, poor women who couldn’t afford birth control, and sexual assault victims, women had ready access to birth control through a medical professional, a local pharmacy, or a convenience store that sold condoms. Roe was settled law, and I did not foresee women’s reproductive rights ever becoming the burning social or political issue it has become. The recent SCOTUS decision shocked me into giving the issue much more serious thought.

This said, while I believe the Catholic Church has done much good in the world, I have always profoundly disagreed with its view of women. By opposing both birth control and abortion the Church is forcing Catholic women into lives as servant wives and baby machines, which I view as institutionalized slavery and morally wrong. It doesn’t take a mental giant to figure this out, so I don’t know who the Church thinks it’s fooling?

Speaking personally, I never took the Church seriously on this issue until solid Guttmacher Institute data revealed that more abortions are performed on Catholic women, who are forbidden from using birth control, than on women identifying with any other religion. There isn’t a woman alive who doesn’t far prefer preventing a pregnancy over terminating one, but the Catholic Church, by trying to have it both ways, is forcing women into abortions, and that’s criminal.

The patriarchal Catholic church is a powerful political lobby that was a major player in the assault on Roe that ultimately resulted in a major blow to women’s reproductive autonomy. I find the idea of men, especially supposedly celibate priests, claiming to protect the unborn by insisting women must sustain pregnancies they either don’t want to sustain, or will endanger them, a huge and profoundly moral problem. Unless these men are willing to financially and emotionally support these babies, and their mothers, for the next 18 years, they don’t get to decide whether a woman sustains a pregnancy. Because I strongly believe reproductive rights are a women’s rights issue that men are NOT entitled to a vote on, I decided staying silent, thus granting men that vote, wasn’t an option.

As women’s reproductive rights moved from the personal to the political, my firm belief in women’s reproductive autonomy morphed into a moral obligation to stand up to the religious and political patriarchy who has the silly, badly mistaken notion that they have the right to legislate women’s reproductive health and other personal choices. They won’t give up on this idea until women force them to give it up. Fearless is the story of how one woman nearly succeeded in doing this.

Christina: Let’s talk about the main character, Sr. Maggie Corrigan. “By making the protagonist a nun,” you said, “I hope this story will inspire the next generation of both Catholic and non-Catholic reproductive rights activists, because this fight is far from over.” Do you think any other characters could have told the story as well as she did? Did you consider any other characters than Sr. Maggie to take up that mantle?

Paula: This novel is inspired by a true story, so I did not consider a different character as the protagonist. A nun, as an “insider,” is a powerful model of the courage it takes to stand up to the Catholic patriarchy and advocate for women’s rights. Whether or not the patriarchy listens is, of course, another matter, but Maggie, cleverly using the “Lysistrata Method” (withhold something a man wants until he gives you what you want) found an effective way to get their attention. Her approach is easily adaptable to other situations and policies men try to force on women that are not in women’s best interests.

Christina: You alluded that you don’t think Fearless has found its audience yet. Who do you think is the best audience for the book? What message do you want them to take away from it? What can readers do to help the book find that audience?

Paula: I’m not sure why I would’ve alluded to that because given the publicity surrounding Roe, I’ve always believed the book had a natural audience. The waiting lists for the book in library systems across the country who have it are, in some cases, lengthy. I also receive Facebook messages from readers fairly frequently, and some reach out through my web page. So, the book is definitely being read.

What I may have been referring to is that while there has been a lot of media attention to the Roe decision, overall, rather than lasting outrage, it appears women generally blew it off, except in the public policy sense, and set about figuring out ways around it. In my view, this is the perfect response in the short term. The longer term, public policy response will take years, and women can’t be expected to wait for all this to play out, so in the meantime figuring out how to best deal with the repercussions from the stupidest, most misguided decision in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court is very important.

Notably, in many respects, the decision hasn’t had the huge negative impact most advocates for women’s reproductive rights thought it would, nor has it appreciably affected abortion rates, which had already been declining for several years. What the decision has done, depending upon zip code, is affect some women more than others because, at its core, it discriminates against poor women and women who suffer unequal from access to reproductive health services…but women are smarter than the men making these decisions and are quickly figuring out how to deal with this.

Fearless’ best audiences are women, the men who love and care about them, and anyone who takes on the difficult battle for social change. Its chief message is to never allow political self-interests or patriarchal religion to drive decisions about women’s lives, and to do whatever it takes to resist any threat to this right in all ways possible. I hope Fearless inspires more women to take up this challenge.

Christina: I’m a former Catholic who holds beliefs similar to yours, and I applaud your willingness to speak up. Did you have any reservations about being outspoken about the patriarchal nature of the church and its perceived shortcomings?

Paula: Absolutely no reservations whatsoever. Although educated in Catholic girls’ boarding school, I also had a very strong, very positive relationship with my dad, who always encouraged me to think for myself and not bend to the will of others. By the time I was a teenager I had figured out that the Catholic Church wasn’t entitled to the last word on women’s reproductive, or any other rights. I never accepted the idea that a cabal of middle-aged men in Rome had the right to tell women how to conduct any aspect of their lives, and by agreeing with me, my dad gave me the confidence to say it.

I find it discouraging that Catholic women don’t stand up to the Church’s intrusion into their private lives and marriages. By remaining submissive, these women are surrendering total control of their lives over to a patriarchy whose own best interests always supersede their own. This makes no sense to me. A male dominated institution is defining women’s lives instead of women defining their lives for themselves. Speaking as a sociologist who views religion as setting society’s moral agenda, my view is that any religion that does not view women as equal with men and entitled to control over every aspect of their lives is dangerous because it invites great social and political harm to everyone…and only gets away with it because women allow it to happen.

The bottom line is the Church won’t voluntarily surrender its power over women; women have to claim it, and I often wonder why they don’t. What are they really afraid of?

Christina: A forthcoming book is The Light Unseen, which once again features a member of the Catholic Church, this time a priest. How does this book differ from Fearless? How is it the same? What inspired you to write the book?

Paula: The Light Unseen is nothing like Fearless and was not a story I was intending to write, but I wasn’t intending to write Fearless either. Instead, it seems that both stories wanted to be written and for some mysterious reason chose me to do it.

Regarding The Light Unseen: I’ve never been interested in genealogy but for some mysterious reason, one Sunday afternoon in the midst of COVID I did a little sleuthing about my mother’s family, about which I know almost nothing. I discovered that my great grandmother immigrated to the US from Germany alone, passing through Ellis Island early in the twentieth century. I also discovered that over 300 records pertaining to the family she left behind in Germany end in Holocaust data bases. This meant she was a Jew, and because Jewish heritability is matrilineal, it also meant I am a Jew, which didn’t surprise me too much. I was quite excited about verifying something I already had some evidence of, and Judaism has always made sense to me, so it seemed like I’d finally, and gratefully, found my way home in the spiritual sense.

This said, having lost distant family members in the Holocaust is very deeply unsettling, but also explains some things I’ve wondered about and never understood. The question in my mind, which is impossible to answer, is why my great grandmother, and subsequent family members in America denied being Jewish? Looking further into this, I discovered that Jewish denial wasn’t all that uncommon, for good reason at that time. The Light Unseen emerged out this context. The Catholic priest provides a romantic twist to the story, but he is not a major character.

Christina: Your nonfiction work has centered extensively on another social justice topic: poverty. Where did your passion for the topic originate? Any tips for what we as a nation can do better to reduce the disparity between the rich and poor?

Paula: Poverty is a political problem, not a personal failing and from an early age I was taught that those of us who are born into more fortunate circumstances than others have a moral obligation to ease the burdens of the struggling poor. In other words, caring for the poor is a moral imperative, and is foremost a very Jewish concept. Pleading the cause of the poor and disenfranchised is not, for me, a passion so much as deeply felt obligation that flows from Tikkun Olam, the Hebrew mandate to use your life to make the world better. This is what I try to use my ability as a social scientist, and as a writer, to do. Everything I write aims to convey a social message that promotes a preferential public policy option toward the poor and less advantaged.

More specifically, I was seven or eight and walking down the street in San Francisco with my dad when I saw my first homeless person. When I asked, my dad said the person was just “down on his luck.” The image stuck with me, eventually evolving into the question of why, in a nation as affluent as ours, anybody ends up down on their luck? Homelessness became one focus of my career in poverty research and illustrated America’s remarkable ability to blame the victim as a convenient excuse for ignoring the poor and socially disadvantaged. I also gained a better grasp of the challenges poor women in particular face, and it became clear that good public policy would solve most of these problems, so I began, both as a research professor and later, as the director of an academic poverty research center, to use my research findings to try to influence political agendas. There were small victories, but an all-out war on poverty isn’t winnable, because poverty as a social condition in capitalist-driven America is not a solvable social problem.

In terms of what the country can do to ease the disparity between the rich and the poor, there is plenty the country could do, but a great many things conspire against doing it. America worships the god of free-enterprise, profit-motive, capitalism. That economic philosophy only works when there is a disadvantaged underclass to provide the cheap labor needed to produce goods and services that generate large profits. It’s an economic system and philosophy that flows from greed and, for nearly 300 years, has worked quite well for those who have been able to make it work. These beneficiaries are the power brokers and decision-makers, and there is no reason for them to change a system that benefits them tremendously.

In other words, America needs a poverty class of poorly paid workers to maintain a profit-driven economy. Until that changes, which is extremely unlikely, there will always be huge income disparities in this country. Americans don’t have the political will or moral commitment to support public policies that obligate the government to ensure all citizens enjoy a minimally decent standard of living that includes basic health care, access to quality food, affordable housing, adequate childcare, and free technical skill education. Concern for the common good over individual gain is not an American value or a public policy priority.

This doesn’t mean we can just accept this social, political, and moral flaw and stop trying to change it, because we can’t. We have to keep trying to change it. Miracles are always possible!

Christina: I love that you started your writing career with a letter to the editor when you were seven. which asked for annual Christmas fund donations to be used to buy shoes for the “impoverished children of Hispanic migrant workers in California’s Central Valley.” Do you remember how it felt to read your letter on the front page of the San Diego Union-Tribune? Do you still get that feeling when you publish a piece of writing?

Paula: I was seven years old when I wrote that letter and the only thing I recall about it now is my dad showing it to me when it was published. I completely forgot about it until I found the newspaper clipping in his wallet after he died forty years later, and I realized how much it meant to him. While I obviously didn’t realize it at the time, that letter apparently launched an ongoing, fairly successful side career writing letters to the editors of various newspapers, advocating a more liberal social agenda.

Story writing is hard work and when something I write is finally in print, mostly I feel relief. I am satisfied that I wrote the best story I could write at the time I wrote it, but whether it is a good story is for others to determine. Even when the reviews are great, or I win an award, I view these as recognition for the work or the subject, not as recognition of me, personally, and there is a difference. I view myself as the instrument through which stories tell themselves, and I’m not inclined to take credit for something that wasn’t my idea. This might seem like hair splitting but I don’t see it that way because who I am as a person and the work I do are distinctly separate.

Writing as a creative endeavor is similar to being as a social scientist: an idea comes to me, I configure a research question and a method to further explore the idea, then get out of the way (i.e., check my ego at the door) and let the findings reveal themselves, and some results are more interesting than others.

A story evolves from an idea that just pops into my head one day and won’t leave until I eventually find a way for the story to reveal itself however it wants to. The only thing I insist upon is that it contains a worthwhile social message. After it is released into the world, I tend to forget about it because the story takes on a life of its own over which I have no control.

What I can admit to is that something outside myself compels me to write. I’ve been doing it since first grade, can’t imagine not doing it, and have worked hard to configure my life accordingly. However, I am very poor at shameless self-promotion which, more and more, is a core requirement of a successful writing career.

Christina: One of your bios states that you’re a “self-proclaimed fire-breathing feminist and life-long social justice advocate for women.” That’s a terrific description. How else would you describe yourself? How would your friends and family describe you? Is there a descriptor you aspire to embody but aren’t sure you will?

Paula: I never speak about or for my friends or family, and don’t like speaking about myself, so this is a difficult question to answer. But, I’ll try.

I am opinionated, strong-willed, independent, mechanical, unafraid to say what I think and am not invested in whether others agree with me. Despite this, I am in a successful, long-term, by all accounts exceptionally happy marriage to a very supportive husband who is a former trial attorney and award-winning writer, is willing to do laundry and doesn’t expect me to cook. Another positive in my favor is our dog also likes me and comes when I call him.

When I was an active academic, I had several colleagues who seemed to enjoy working with me, mostly because I am a well-trained social scientist with a solid sense of the absurd, had a lot of grant money, and most important of all, even though I don’t drink myself, favored holding research team meetings at Duggan’s Bar on Friday afternoons. They would probably say I am funny, intelligent, and don’t suffer fools gladly, especially if they are the fool I’m not suffering that day. My graduate students would say I am intense and difficult to please. My friends often turn to me for advice. I rest my mind by watching college football or well-written TV sitcoms and only take seriously things that actually bear taking seriously.

However, writers are, by default, self-absorbed introverts who live in their heads, need a lot of dead time, and far prefer their own company over anyone else’s. All of these are traits I definitely need to work on.

Paula can be found in multiple places!

Website: https://www.paula-dail.com/

Facebook: @paula.dail.73

Goodreads: Paula Dail

Thanks to Paula for agreeing to this interview! If you know of an artist, author, or podcaster who’d like to be featured in an interview (or you are an author who would like to be featured), feel free to leave a comment or email me via my contact page.