Invested in Telling the Truth: An Interview with Deborah A. Lott

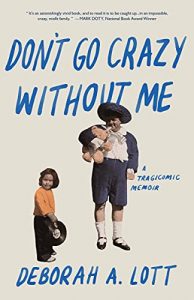

Stories about families—fiction or nonfiction—interest me greatly, which is part of the reason I wanted to help shed light on Deborah A. Lott‘s Don’t Go Crazy Without Me, which released in April 2020. Mark Doty, memoir writer and National Book Award Winner, wrote of the book, “It’s an astonishingly vivid book, and to read it is to be caught up, just as the writer was, in an impossible, crazy, misfit family,” and Hope Edelman, author of Motherless Daughters, said, “[Lott’s] keen insights into the dynamics of her quirky, unforgettable family, and into family dynamics in general, make this book bound to be a classic.” This is Deborah’s second book, the first being In Session: the Bond between Women and their Therapists, which offers “an unprecedented look at psychotherapy from the perspective of clients interviewed by the author.” And she’s no stranger to other forms of publication either, as her work has been featured in multiple online and print outlets, including Alaska Quarterly Review, Bellingham Review, Black Warrior Review, Cimarron Review, Rumpus, Salon, and more. She teaches creative writing and is a faculty adviser for Two Hawks Quarterly, which means she has little spare time on her hands. I’m grateful for her time and attention in answering my questions.

Stories about families—fiction or nonfiction—interest me greatly, which is part of the reason I wanted to help shed light on Deborah A. Lott‘s Don’t Go Crazy Without Me, which released in April 2020. Mark Doty, memoir writer and National Book Award Winner, wrote of the book, “It’s an astonishingly vivid book, and to read it is to be caught up, just as the writer was, in an impossible, crazy, misfit family,” and Hope Edelman, author of Motherless Daughters, said, “[Lott’s] keen insights into the dynamics of her quirky, unforgettable family, and into family dynamics in general, make this book bound to be a classic.” This is Deborah’s second book, the first being In Session: the Bond between Women and their Therapists, which offers “an unprecedented look at psychotherapy from the perspective of clients interviewed by the author.” And she’s no stranger to other forms of publication either, as her work has been featured in multiple online and print outlets, including Alaska Quarterly Review, Bellingham Review, Black Warrior Review, Cimarron Review, Rumpus, Salon, and more. She teaches creative writing and is a faculty adviser for Two Hawks Quarterly, which means she has little spare time on her hands. I’m grateful for her time and attention in answering my questions.

Christina: You describe Don’t Go Crazy Without Me as “The coming of age story of a girl who grows up under the magnetic spell of her outrageously eccentric father.” For those of our readers who haven’t yet read the book, can you give us a mini-synopsis of the story?

Deborah: The book alternates between the story of my growing up from ages 4 to 17, and current day episodes that show the ways my history continues to reverberate in my adult life. We were a leftist, hypochondriacal, loud Jewish family in an isolated Southern California suburb inhabited primarily by Christian Republicans. My father was self-dramatizing, obsessed with death and disease, prone to intense moods, addicted to painkillers, and also often hysterically funny. He was a shape-shifter, one moment the wise lay rabbi of our tiny Jewish community center, the next dressed up as Little Lord Fauntleroy and talking babytalk. I adored him and identified with him. When my paternal grandmother died, my father descended into a pathological grief that culminated in a psychotic break. I nearly followed him, having developed some crazy ideas and obsessions all my own. Politics, sex, and healthy grief saved me. One of the questions the book asks is how do we break free of our parents and forge our own identities even when we don’t have good role models? If we grow up in a community from which we feel marginalized or alienated, how do we find the people who make us feel seen?

Christina: In the prologue of the book, you write, “I can’t help but wonder why I feel compelled to tell [the story] as if I could still get it right.” Did you get it right? Is there anything you might change about the book itself or how you told the story?

Deborah: I think the metaphor of a photograph applies to any memoir: take a photograph of any room at any moment in time and the photo will come out differently depending on where you place the camera, the light in the space, the length of the lens, even the mood of the photographer. I think that there are ten other versions I could have told. Every detail included, or left out, changes the story. I think there are probably a hundred different ways any of us could tell the story of even one day in our lives. That’s the beauty and the challenge of memoir.

Christina: Did you ever consider fictionalizing the story? Why did you choose to write memoir in particular? Did you ever have any doubts about your decision?

Deborah: There were times when I wished I was writing fiction and had the distance from the material that fiction might afford. I’ve written some short stories and flash fiction, but my form is really memoir, my material my own life and consciousness and experiences.

Christina: In a review of the book for Brevity, Claire Donohue Roof says, “Eventually Lott chooses love over grief and loss, and, in the end, it redeems her,” and that she “highly recommend[s] this book for its honesty, its humor, and its bravery.” What was your writing process like so that honesty, humor, and bravery could shine through? How did you find the right balance so that the themes of grief and loss didn’t weigh the reader down?

Deborah: I’m a firm believer in multiple drafts. Many, many, many drafts. The humor was probably mostly there even early on because that’s one of my basic coping mechanisms. There was a lot of humor in our family—my dad in his more manic moments—could be really funny. It’s also inherent in my cultural heritage, the way Jews survived the pogroms and other major indignities. The truth is I’m sometimes funny without even knowing it; I can feel as if I’m saying something in a pretty melodramatic fashion until I realize the person I’m talking to is laughing. The line between comedy and tragedy is thin. The honesty comes from just pushing the material, saying the thing you’re most afraid of saying, following your shame wherever it leads. And I’m really invested in telling the truth—I hate lies and deception and evasion. I can’t even bear to watch a magic show.

Christina: Are you like your father at all? Do you find yourself doing things that he might? What’s one trait you admire about him that you wish you possessed?

Deborah: Although I had to separate my strong identification with him to survive psychologically, I am a lot like him. I resemble him physically and have a lot of the physical afflictions he suffered from. The preoccupation with illness that I picked up via nature or nurture, persists. I also like public speaking and am pretty good at it and my father could transfix an audience with his voice. I can’t really think of a particular trait of his that I wished I possessed—maybe the ability to have a completely uninhibited good time without self-consciousness. The thing is, even most of his admirable traits had their downsides. A completely uninhibited good time in public can also get you into trouble.

Christina: The book was released at one of the worst possible times. How do you think the pandemic affected that release? Is there anything you could have done differently? Did you learn some lessons for moving forward with book releases regardless of what’s happening in society?

Deborah: None of the traditional ways of promoting a book—a tour, bookstore readings, a book party—could happen because of Covid. Many bookstores were closed. I wound up doing a lot of zoom events and readings. I began to teach two classes online for anyone who bought my book: one on writing about trauma and the other about writing childhood. The upside was meeting people I never would have met otherwise, and being able to read with folks all over the country. Selling books during Covid required a lot of scrambling. I’m excited every time a reader finds me and tells me that my book meant something to them, reached them, enabled them to remember or understand their own coming of age differently. That’s really all you can hope for.

Christina: Along with writing, you teach writing, including courses that address trauma and childhood. What’s the first step to being able to write about trauma? Do writers have to prepare themselves? Do you have any tips for emerging writers that you could share?

Deborah: Writing about trauma often allows us to process the event(s) in a new way. It can be therapeutic. It can also be painful and put you right smack back emotionally in the middle of a traumatic event. I always tell students to start small—just write about what you can tolerate writing about and titrate your exposure. Tell yourself you’re going to write for 5 minutes or 15 minutes and then have a plan for re-entry into your current world—a scheduled walk or phone call or meditation. Remind yourself that the trauma does not define you: you are no longer the victim of the event, you are the teller of the tale. You survived.

Christina: What’s next for you?

Deborah: I’m writing about my perplexing relationship to my body, and what is currently known and believed about the mind-body connection in sickness and health. This memoir will be partly the story of my own experiences with illness and doctors and medical institutions, and part research-based, covering some of the new understandings of how mind and body interact. It’s a challenging project because so much remains mysterious. I try to balance the writing with teaching and working with other writers as a developmental editor.

Deborah can be found in multiple places!

Website: https://deborahalott.com/

Facebook: @deborah.a.lott

Twitter: @deborahlott8

Thanks to Deborah for agreeing to this interview! If you know of an author who’d like to be featured in an interview (or you are an author who would like to be featured), feel free to leave a comment or email me via my contact page.